Going beyond interdisciplinarity

In the research world interdisciplinary is a buzzword. Research applications are full of requests to fund interdisciplinary work. This post explores why that’s a good thing – and how we can go even further.

Usually, research is called interdisciplinary if it involves collaboration between staff from two or more different university departments. The researchers say interdisciplinary work is needed to tackle complex problems that require multiple perspectives and to share ideas between subject areas.

It’s not easy. Researchers engaged in interdisciplinary work quickly find that their counterparts care about different things, have different ideas about how things work and operate in different ways. On a practical level, communicating can be difficult because of differences in language use.

Climate change is a classic example of a complex problem that requires interdisciplinary inputs. Chat-GPT even cites it as the number one example. Understanding climate change requires physics and chemistry. Understanding what to do about it requires the social sciences, but also life sciences and other less obvious fields, such as humanities.

But how much climate change research is actually interdisciplinary? The IPCC’s big reports do a good job of separating out the different bits, so don’t encourage interdisciplinary work. A quick skim of recent journal articles (and their author lists) suggests that most come from a single discipline. Some of these ‘interdisciplinary’ research projects turn out to be people doing their own things without much interaction between the disciplines – which is termed ‘multidisciplinary’.

Let’s keep it simple?

Does this matter? Some people would argue that we are better off letting each expert look at their own area. We can solve climate change piece by piece, gaining the benefits of each researcher’s specialist expertise, without making them learn new ways of thinking and communicating.

For some problems it might work. Kids are taught to break down maths problems to make things as simple as possible. Computers with multiple processors do the same so they can solve each part in parallel – giving faster results. Why not apply the same logic?

The thing is, it doesn’t work for complex problems, in which the components interact. School kids cannot break down equations where each part affects each other part. The rules for parallel processing in computers are strict. There is no way around understanding how the interactions work. That means having those difficult conversations.

It’s all about the ideas

And from those difficult conversations we get new ideas. In 1934 the famous economist Joseph Schumpeter described how new ideas come from the ‘novel combinations’ of old ideas. In the late 19th century, Thorstein Veblen (another economist) called the same process ‘cumulative causation’. Beyond a primitive level where we take our ideas from nature, new ideas come from human interaction.

That’s fine, but could we not get new ideas from interactions within a single discipline? This does happen of course, but the benefits tend to be more marginal. Putting two specialist things from a certain field together usually leads to something also specialist within the boundaries of the same field. It’s like the branch at the top of the tree splitting – we get twigs rather than big new branches.

Take one of the biggest ideas of all – evolution. Wikipedia describes Charles Darwin as a naturalist, geologist and biologist. That’s already interdisciplinary, but he developed his theory of evolution from work on human welfare by the economist Thomas Malthus. Not long after Darwin’s death, Thorstein Veblen tried to bring evolution back into economics.

That field became known, in the early 20th century, as Institutional Economics (nowadays ‘old’ institutional economics). The dominant field, Neoclassical Economics, borrowed the first law of thermodynamics from physics. Since the 1980s, the idea of evolution in economics has come back, especially in complexity-based work. Again, biologists and physicists have played important roles.

How does ICENS lab fit into this?

ICENS lab recognises that a) both climate change and climate change policy are complex issues that cut across disciplines, and b) we need new ideas for how to deal with the problem. ICENS lab therefore sets up a platform for interdisciplinary work (not limited to research) on climate issues placed within a sustainability perspective. It also encourages diversity in economic thinking so that interdisciplinary work is stimulated through the ‘partnerships’ that different schools of economic thought have with various other disciplines.

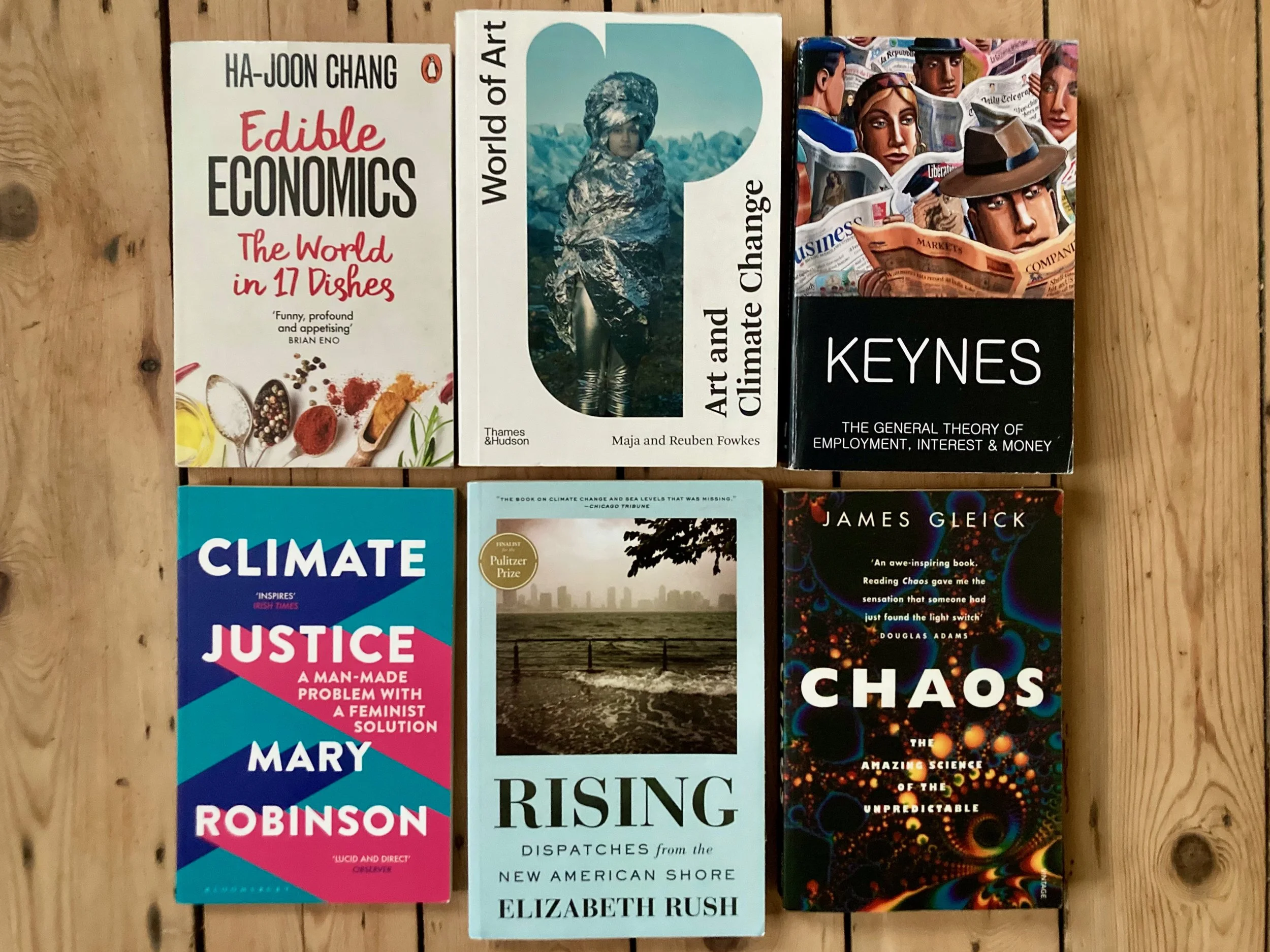

Where ICENS lab goes beyond other interdisciplinary efforts is by stretching the boundary of interdisciplinarity. What could economists learn about climate change and climate change policy from the world of the arts and humanities? And vice versa? This has not yet been explored much – for instance, a quick search on Google shows that art is used to make people care about climate change, but less to think about economics.

We could do a lot more. Among other things, art is a way of expressing ideas. It could help us communicate, learn and see the world in different ways. But it could also be a source of new ideas. We don’t know yet because we haven’t tried much.

And it’s not just art. Who knows where the next big idea might come from. But there’s a good chance it will be an interdisciplinary effort like ICENS lab that brings it together.

Written by Hector Pollitt, Senior Economist, 06 October 2025

Photo by Șerban Scrieciu