The interplay of economics and art: Uncertainty and the climate crisis

LEAP lab (Living Experiments in Arts-Science Practice to Re-imagine Sustainability), together with ICENS lab, and with support from CRASSH (Centre for Research in the Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities) organised at the University of Cambridge (23 June 2025), an exploratory workshop on “Experiments in uncertainty and un/knowing: Economics - visual arts perspectives on climate change mitigation”. The purpose was to foster interactions between the realm of economics and that of the arts, two worlds far-apart that typically operate separately, and explore how the arts could help revise and rejuvenate economists’ mental models and understandings of economic dynamics. So that the interplay remained centred, the onus was on the thorny concept of uncertainty, particularly in relation to the climate crisis. The workshop brought together around twenty people (artists, economists, and other researchers working in sustainability) and contained a mix of creative activities and group discussions, balancing between structure and free-flow, between art-making and talking. It is hoped that this was a first pilot initiative and the start of a method, in a series of systematic efforts to connect economists with artists. The overall longer-term aim is to shape arts-driven economics research and practice, and figure out ways in which the arts, through its critiquing and revealing nature, could aid the economics discipline, such that the latter becomes more disruptive, innovative, and less immune to fossilisation.

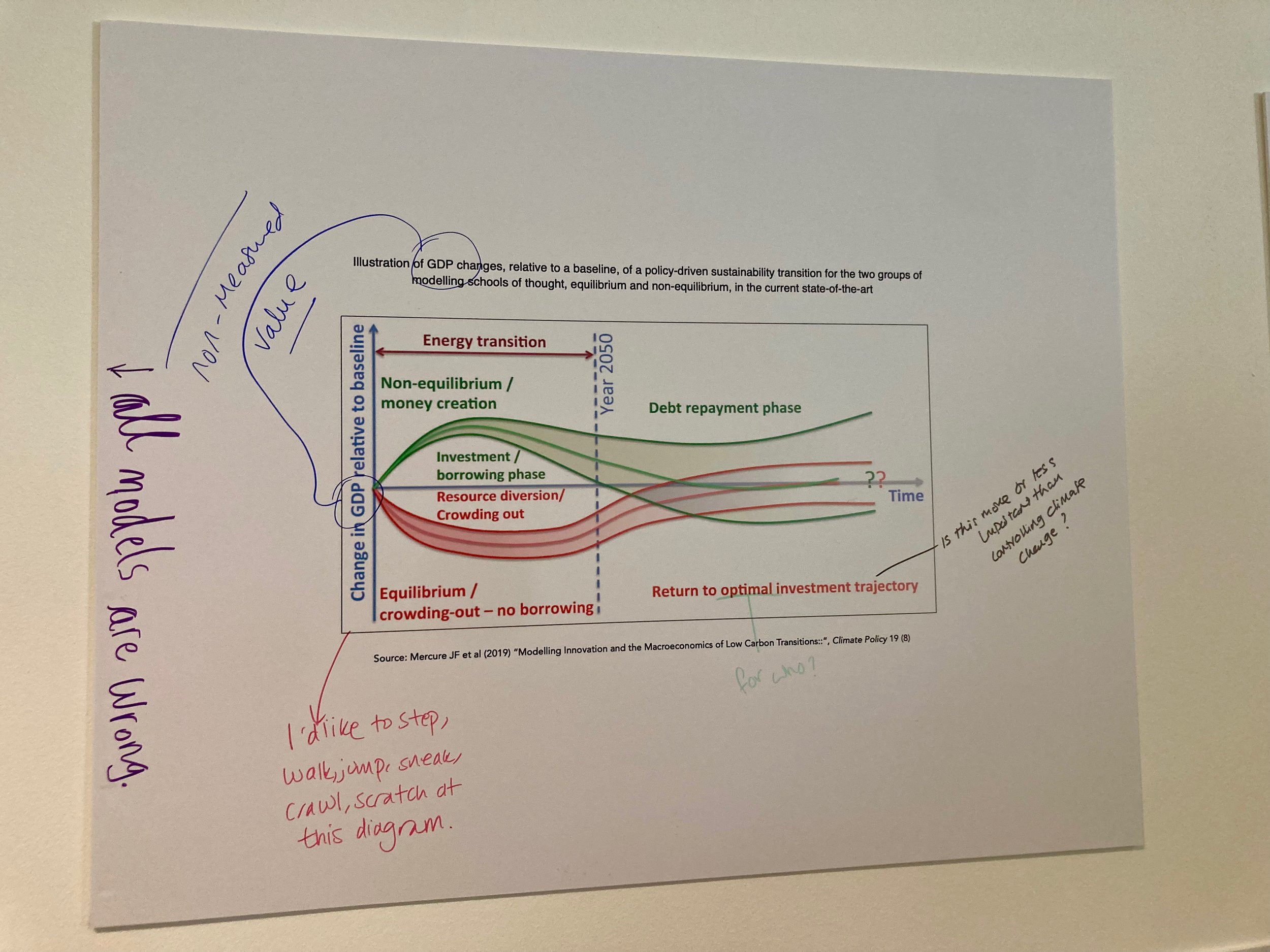

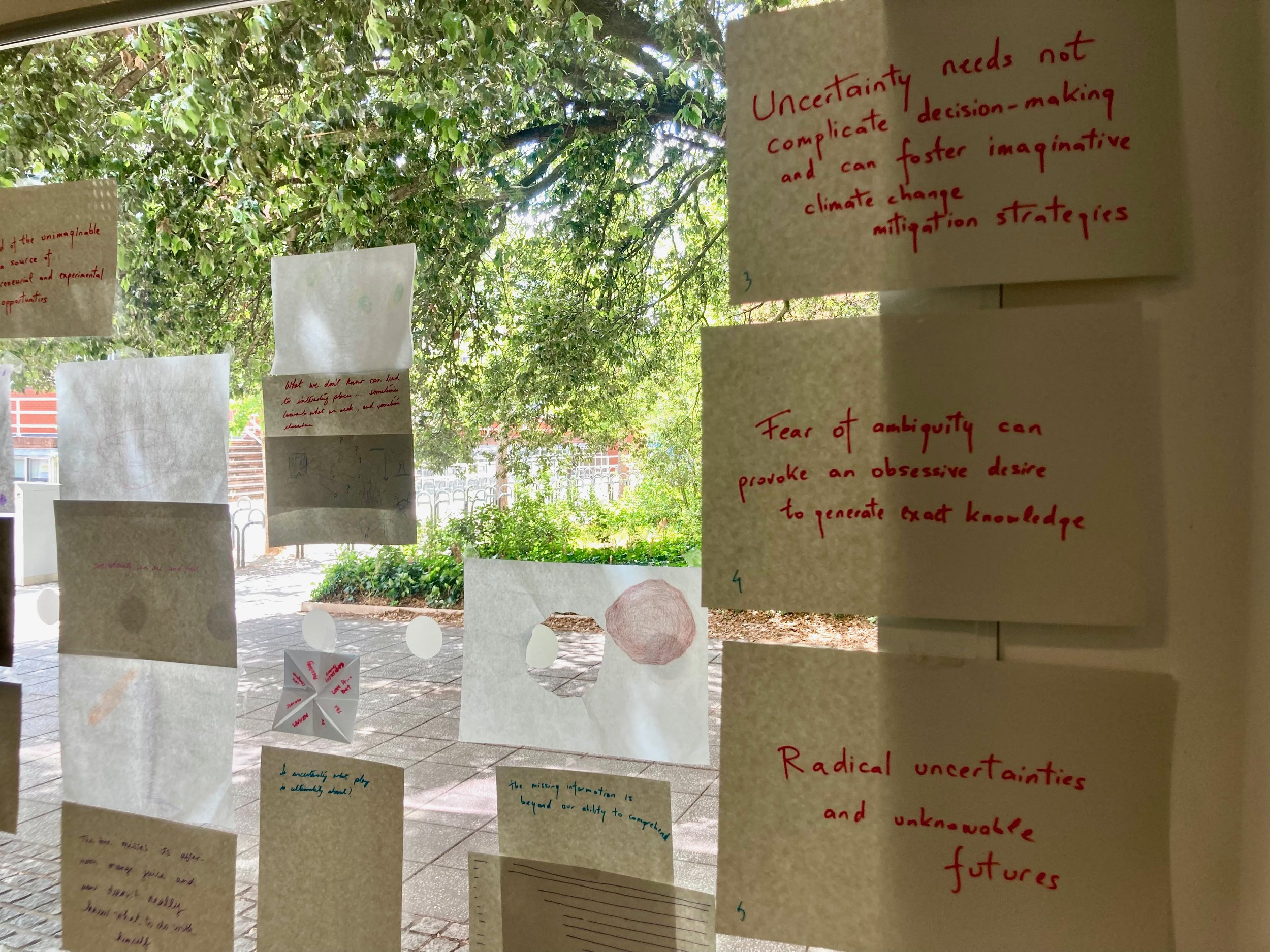

The workshop kick-started with an introduction and a panel discussion based on visual stimuli, drawing a series of artistic photography and analytical images linked to uncertainty and climate economics. The discussions were guided by a group of economists and art practitioners/researchers, and benefited from the fantastic moderation of Sarah Royston, with support from James Norton and students Cassie Ahmed and Julia Toczyska from Anglia Ruskin University. Șerban Scrieciu, the founder of ICENS lab and an economist working on sustainability issues emphasised that mainstream economists typically deal with those dimensions of uncertainty that are knowable and can be placed into the straight jacket of mathematical formalism and probabilistic quantification. Many economists and decision-makers have a fear of ambiguity, uncertainty or multiplicity, as well as an obsessive desire to provide the ‘right’ answers and generate ‘exact’ knowledge. Moreover, uncertainty has often been used as an excuse for poor action on the climate change mitigation front. However, the elephant in the room is ‘radical uncertainty’, which cannot be quantified because not only do we not know what will happen, but also we may not know the kind of events that might happen - so-called ‘unknown unknowns’ or the world of the unimaginable. Șerban argued that radical uncertainty need not be seen in a negative light, but as a generator of entrepreneurial opportunities and excitement. He pinpointed that it is precisely in these areas that art could inspire economists: to explicitly acknowledge the fundamental presence of unknown unknowns, express the ineffable, provide a fresh, creative restart to our understanding of economies, embrace radical uncertainty, and develop a symbiotic relationship with the world of the unimaginable.

Richard Lewney, also a senior economist, chair of the consultancy Cambridge Econometrics (and associated with ICENS lab) argued that economics is poor in being engaged in interdisciplinary work and has been sitting in its own academic bubble. It usually starts with the assumption that everything is known and certain, and then tweak this to allow for some reality. However, uncertainty is not an inconvenience, but is pervasive in our world, and should be the one we tackle head on. He referred to the work of Daniel Kahneman (Nobel Memorial prize winner in economic sciences), which stresses the term of cognitive unease or bias in the sense of being much happier with what we are familiar with. For example, the take up of green technologies is slow partly because these are new and there is a general fear of uncertainty (e.g. heat pumps versus established gas boilers). Economists deal with uncertainty by providing different (low-carbon) scenario pathways to policy makers, which tend nevertheless to be too tight, too well-defined.

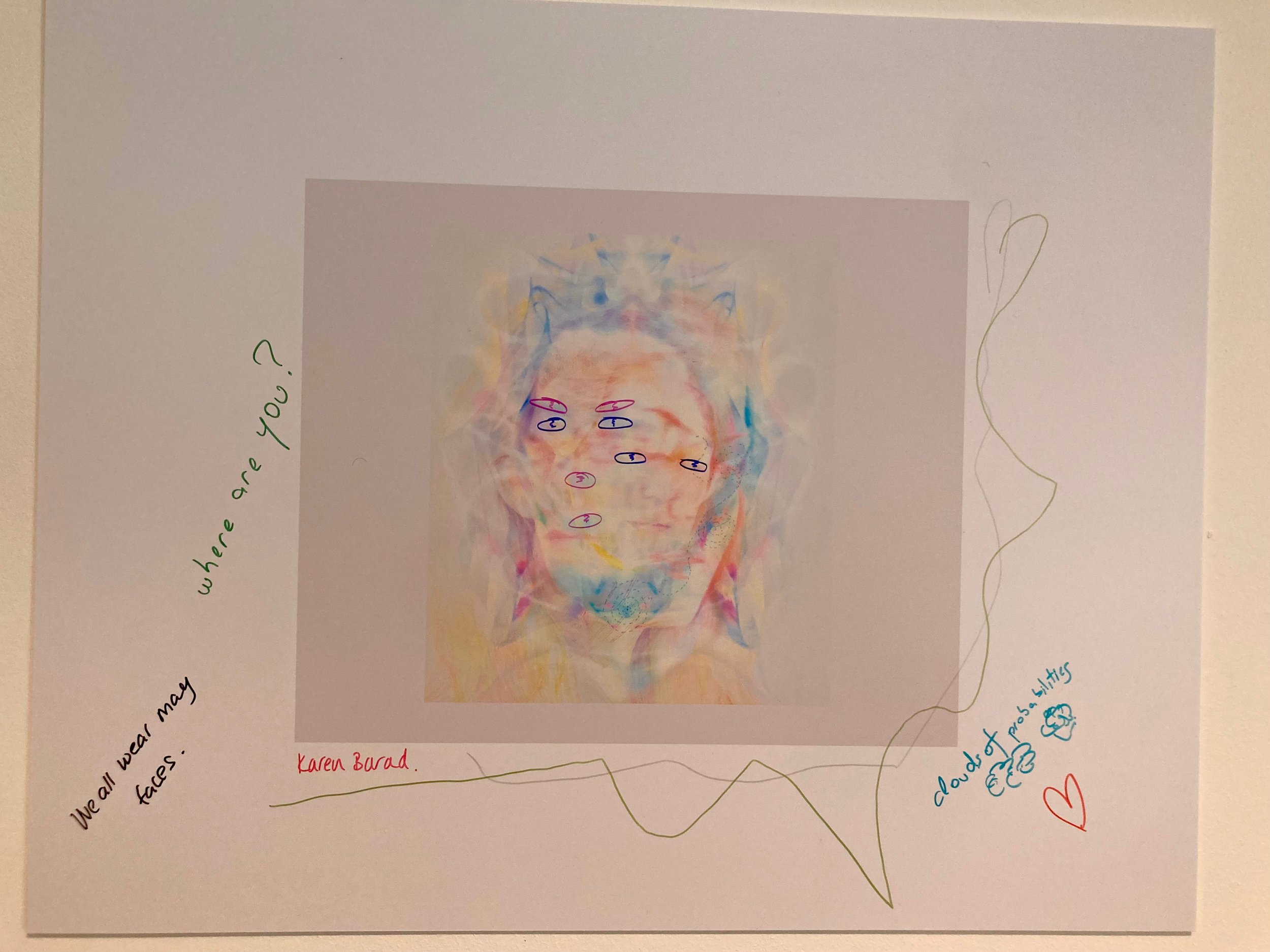

Hanne Peeraer, an interdisciplinary artist and researcher working at the intersection of neuroaesthetics, perception, illusion and meaning-making (and also an ICENS lab associate), asserted that uncertainty is key to how humans perceives our environment. Humans in order to survive constantly look for uncertainty in order to solve it, update its internal model, and feel safer. The human brain thus loves and hates uncertainty at the same time; it is simultaneously an opportunity and a fear. Hanne stated that one of the reasons why the arts is appealing or engaging is because of its ambiguity, because of having too many correct answers that could be possible. She has developed artwork that captures ambiguity and sees how people react to different levels of visual complexity. There needs to be a strong separation between art-making and the way we understand art, uncertainty and the nature of complex systems. Uncertainty is a necessary component for knowledge to arise. However, many science-arts exhibitions tend to be visual representations of still very structured predictable scientific concepts. In order to really think about uncertainty, one needs though to lean into the power of art in generating real uncertainty, and not just explaining something in a different visual or artistic way. The logic of art is thus that of being something that leans into the unpredictable.

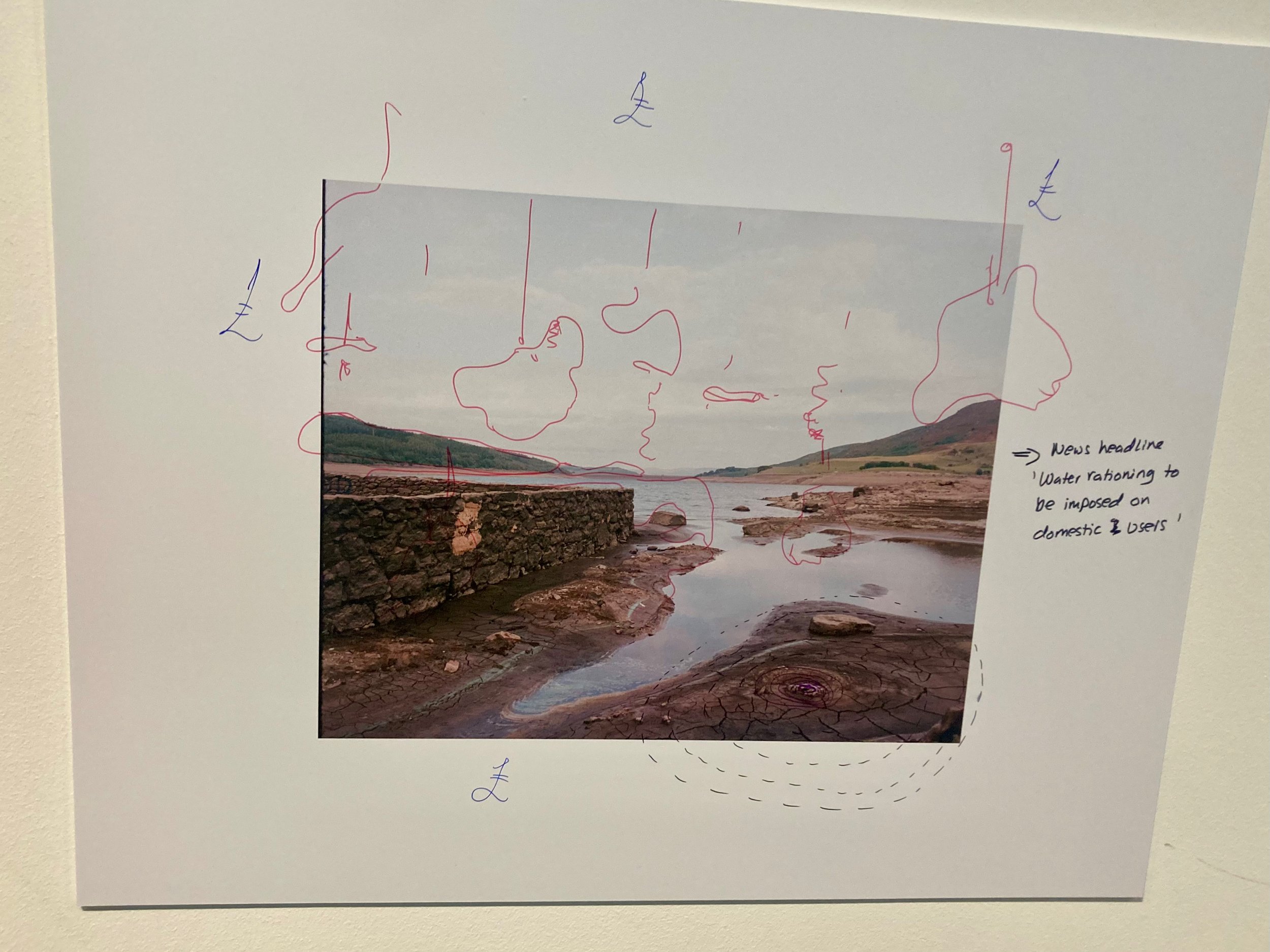

Duncan Wooldridge, an artist and a writer on photography and art, based at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) mentioned that photography has a lot to share with economics, in terms of being risk averse. Most of the images in photography are quite conventional in the sense of having a documentary value, functioning as a record, capture or arrest, are frozen instances. This is partly because the machine and logic of the image encourage a desire for certainty, to control certain technical photographic parameters. However, we need to recognise that there are several aspects in photography that fall outside of our control, that are accidental or speculative. The understanding of what images might do can be stretched, in terms of images having the potential to be anticipatory and speculative in their making. Sian Macfarlane, a photographer also based at MMU looking at water infrastructures, and how photography is a tool that both inhibits our understanding of its histories and its rooting. She is happy in uncertainty, which provides a safe space. Sitting with the unknown is specific to arts practice, since this is how one makes developments in this area. Photography can be pushed into the co-creation of new knowledge. Photography or imagery often communicate climate change through landscape narratives that carry negative connotations, e.g. floods and other disasters of climate change. Nevertheless, there is knowledge to be gained from the climate moments, from the uncertainty or unexpected consequences of climate change that can also reveal opportunities or benefits that arise in parallel with the established problematic of climate change. In this respect, Sian gave the example of a water reservoir in Wales which was initially created to serve Liverpool, but at the expense of flooding a community, displacing people, and completely erasing parts of the Welsh culture. With climate change, the respective area recently suffered from droughts and extremely high temperatures, but the dried up reservoir revealed its history, its former spaces, village, graveyard, and become a site of commune that people started visiting.

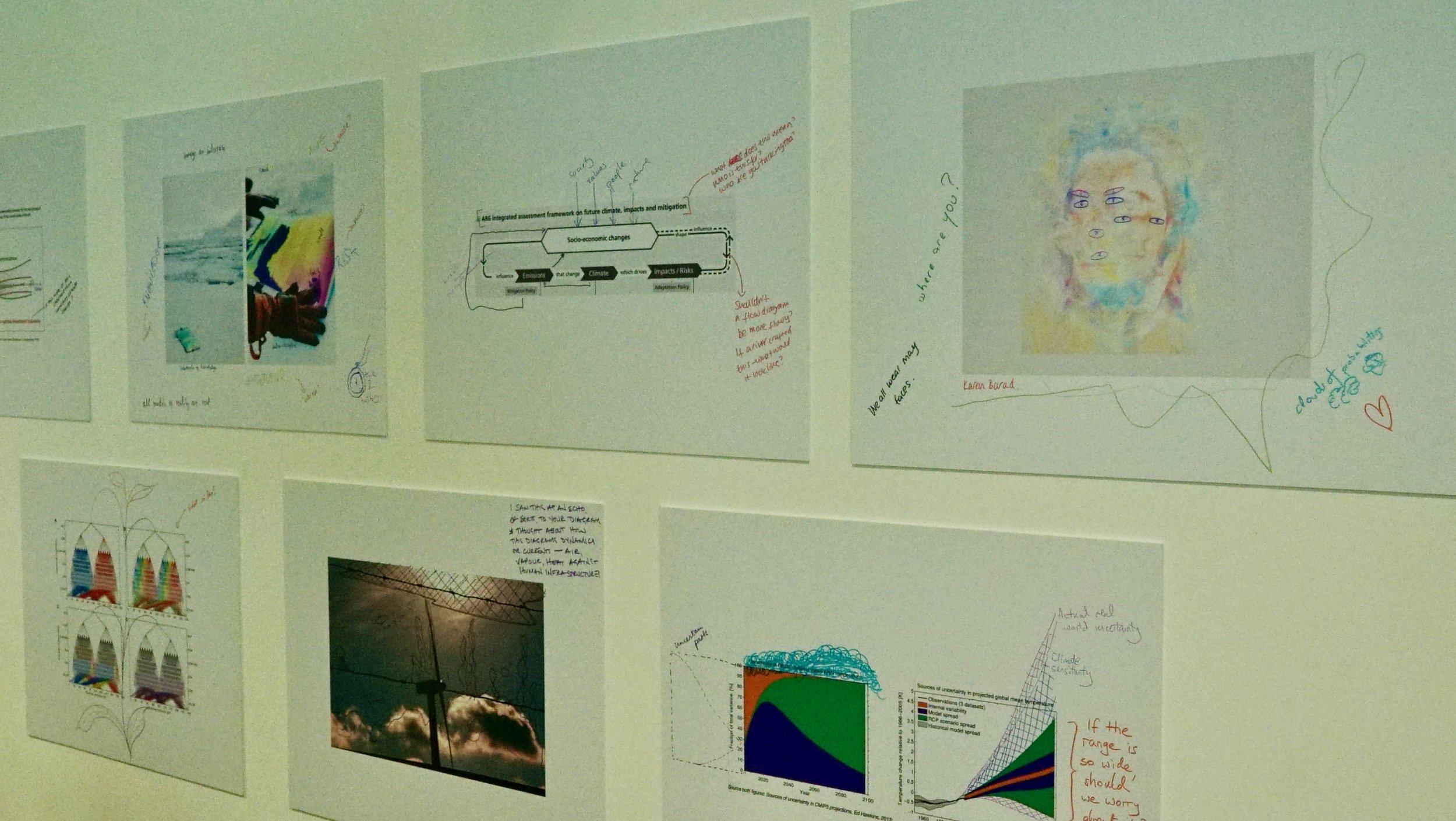

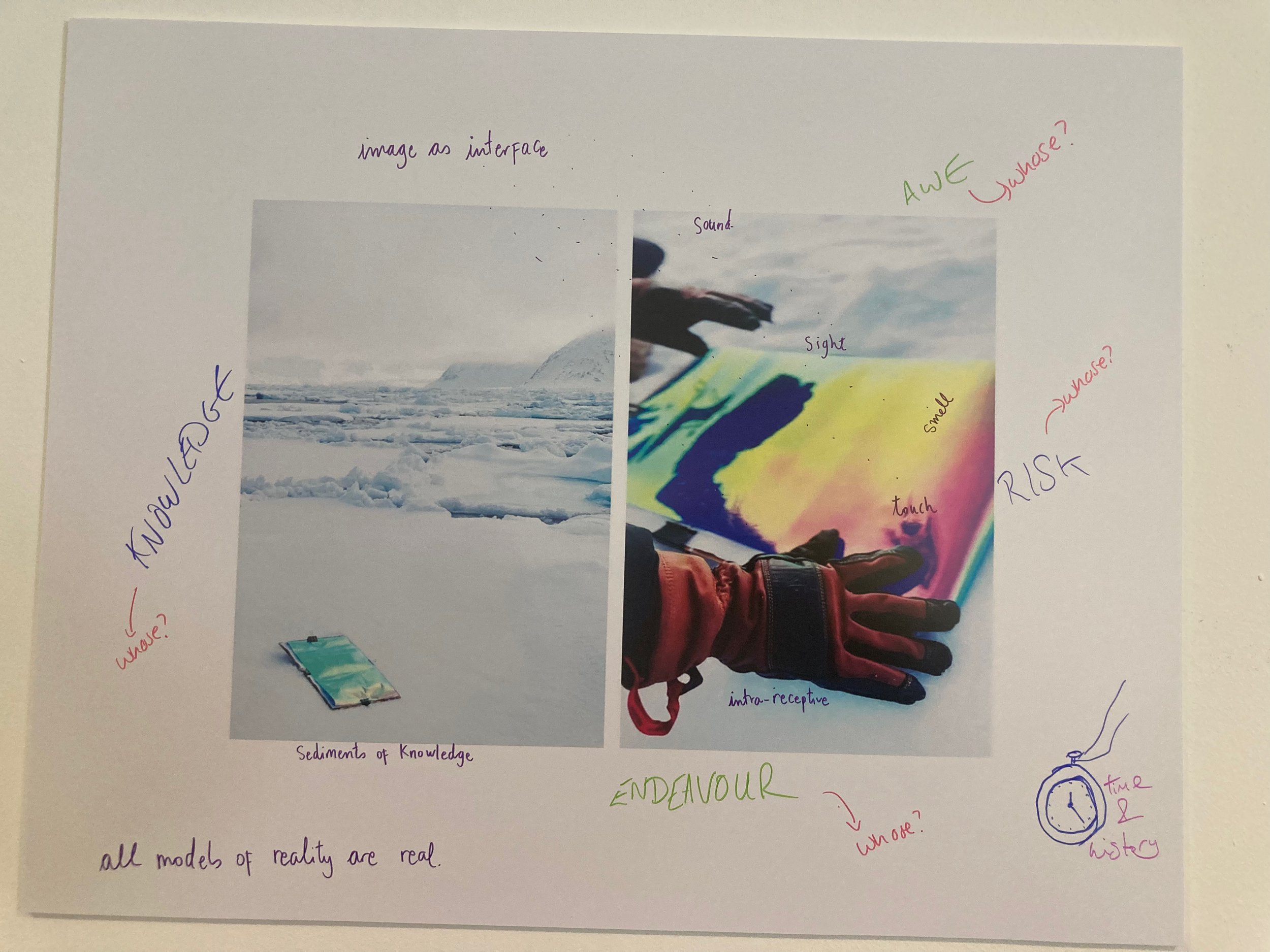

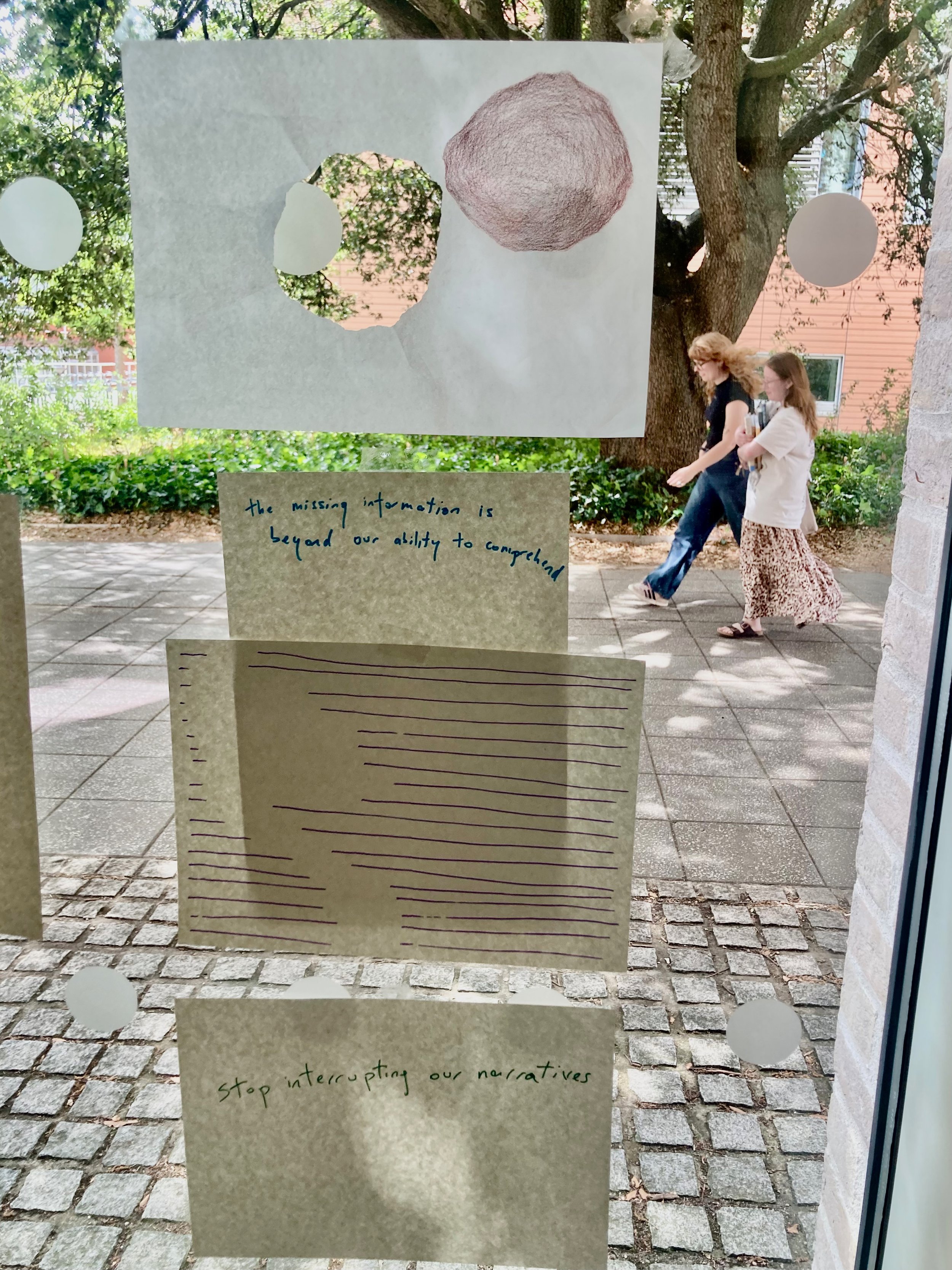

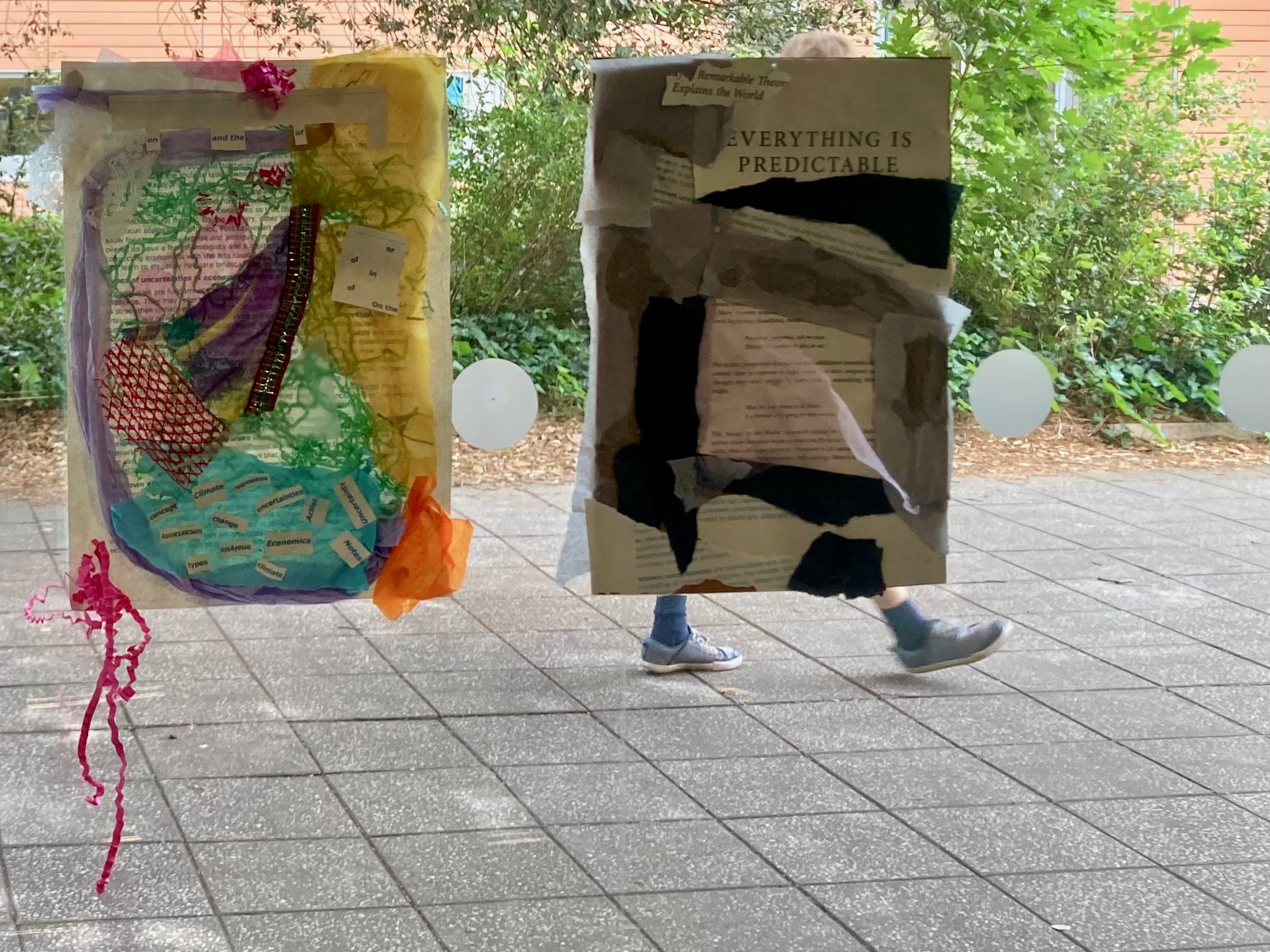

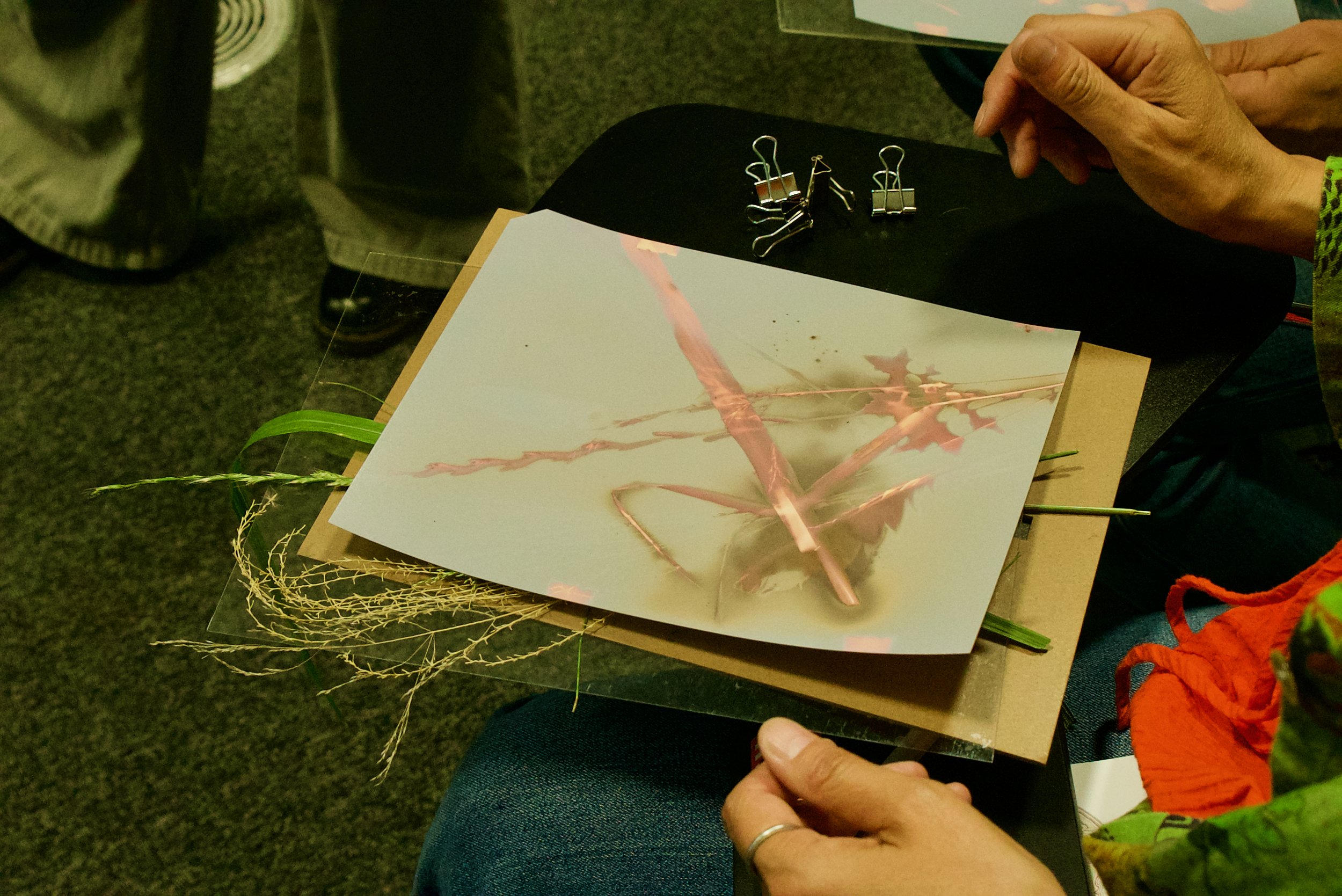

The workshop continued with a series of facilitated arts-based activities (solo and group-based) centred around three creative stations and guided by questions on uncertainty and climate change economics. These included a station led by Richard and Duncan, annotating existing artistic and analytical imagery brought by the panelists and printed on matt photographic paper and framed with wide white mounts, with alternative narratives in the form of questions, statements and drawings. Another station, led by Hanne and Șerban, consisted in starting with written remarks linked to the topic of uncertainty and climate economics (e.g. fear of ambiguity can provoke an excessive desire to generate exact knowledge), with participants first interpreting these via drawings, which were in turn re-interpreted via new wordings, and again drawings, and so on. This mirrored the need to enrich given written narratives or statements and go beyond what is read, seen or visible, in order to generate complementary or new understandings. The third station guided by Sarah and Sian, consisted of making collages that would reflect our feelings, both positive and negative, vis-a-vis how uncertainty and unknowing appear in one’s work. The workshop continued with a collective creative session led by Duncan and Sian that drew on the alternative photographic technique of lumen printing, whereby images are created not with cameras but simply by placing objects on photographic paper and temporarily exposing these to sunlight. The lumen printing photo process plays with chemistry, materials and reactions, and incorporates some uncertainty at different stages - foraging, light photo paper, shifting weather, and producing dynamic images that change over time and are resistant to capture. Moreover, the practice of lumen printing momentarily separates optics from chemistry and can help us understand the nature of the image, as a sensing device, rather than a depicting tool. This in turn may assist economists and decision-makers revise their mental models, in terms of accommodating for and assuming the role that uncertainty plays in our processes of understanding the world and addressing its complex challenges.

The aforementioned creative activities helped shape a safe space, where some of the biases of the economics discipline in their handling of uncertainty and the climate challenge could be explored through the aid of artistic means. The workshop concluded with discussions, where participants shared their thoughts and perspectives on bringing economics in dialogue with the arts world. Participants found value in the workshop idea, content and process, and there was a consensus on some sene of proof that this type of cross-pollination could be useful and is worth investigating further. They also agreed that uncertainty, error and mistake can be sources of learning and inspiration. The arts through its critical lens, open-ended and creative nature, can unpack knowledge, ‘un-know’, and dismantle prejudices and our preconceived understandings of the world. The challenge is though to communicate these ideas to mainstream economists, have the orthodoxy on board, and convince them that there are benefits to be drawn from connecting economics with the arts. The challenge is also to embed art into quantitative economics narratives, and find ways through which the arts could generate knowledge on sustainability and stimulate economists’ creativity.

The arts typically embrace unknown unknowns and have learned to draw on the uncertain dimensions of our world to push forward creativity. In order to solve problems in relation to complex systems that cannot be controlled and known completely, there needs to be uncertainty. As such, economists could learn from artists and accept a certain degree of unpredictability in their work and worldviews in order to explore different solutions, assume the role of radical or fundamental uncertainty rather than try to solve for it. There is also a need to shift the narrative on uncertainty and climate action so that we are excited about the possibility rather than be fearful of the change. The arts could help economists lean into words that are more on the productive, exploratory, positive side, such as ‘multiplicity’, ‘blurriness’ or ‘oscillation’, when relating to the concept of uncertainty. Furthermore, it is easier to break the established patterns and practices in the art world as there is some reward in terms of creativity. However, it is more difficult to do so in the world of economics, and finding the rewarding feedback for the case of economics could help the discipline break new boundaries, at a faster pace. One way of solving for this would be to reflect on the feelings that one is going through as an economist as one does her work - this practice of feeling could be nurtured by art. Another mechanism that would help economists widen their perspective is via education. One could convey in economics curricula that facts and knowledge are less static and often open-ended, that there are less objective truths than typically assumed. The use of the arts would enable students to better live with uncertainty, allow for multiple knowledges, and question what it means to know, and how these in turn may impact our understanding of economies.

Written by Șerban Scrieciu, 18 July 2025

Photo credits: Thanks to James Norton, Julia Toczyska and Cassie for part of the photos